WITCH HUNTS ON BROADWAY!

Broadway is concerned with history repeating itself, so it follows that witch hunts are back en vogue.

Our warnings and historical references to nationalism, misogyny, racism, and Nazism have been steadily recycled in the media and at protests across the nation since at least 2016. Let’s face it: with Trump back in office, despite all the people saying ‘never again’, those of us trying to protect American democracy are looking to change the course of direction.

Once again, America is experiencing dystopian attacks on art, philosophy, knowledge, and emotion. We’ve seen it walk through the door during McCarthyism and the Cold War, internment camps and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; it appears to us today in banned books and plummeting literacy rates, restructuring and removing the committee board at the Kennedy Center, tech moguls controlling and owning traditional media, and AI-generated images, to name but a few.

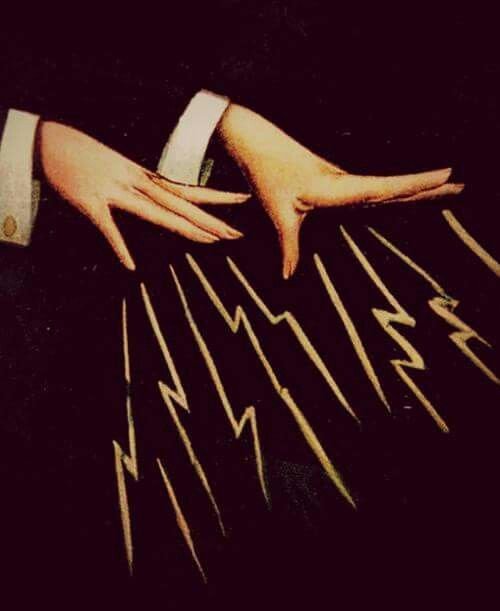

When society is at its most dangerous, or reaching a fever pitch, in swoops an artist. Resistance art is thriving right now, particularly on Broadway, with extended runs and impressive Tony nods from the likes of Good Night and Good Luck, John Proctor Is The Villain and Cabaret. Each reveals a poignant study on individual activism in the riptide of frenzied cultural and political witch hunts. Victims, perpetrators, and bystanders are exposed under the stage lights, and nothing can be assumed. As the unthinkable strikes, it’s not a flash but a slow creep; as the plot unfolds and the challenge against truth or liberation rises, these three plays provide a bevy of responses that we must recognize for survival of our reality.

When I went to see John Proctor, I questioned whether I had purchased tickets to a white lib-dem feminist fest or something with substance. I remembered bits and pieces of The Crucible’s plot from high school, warily eyeing each of the characters as they appeared, determining who would mirror which legendary Salem character.

Set in a small town in Georgia, a group of teenagers navigate coming of age against the backdrop of 2018’s Me Too scandals and studying the aforementioned play in English class. They show us that the John Proctors (now determined by the characters as a perpetrator) are everywhere; our own fathers, friends, favorite teachers, friends’ dads, studio executives who make people stars, men who appear to us like caretakers or leaders in the community and manipulate behind closed doors. Evangelism replaces Puritanism as the deep, culturally entrenched faith that is used as a mechanism for shame, groupthink, and patriarchal hegemony.

Right now, we are witnessing girlhood in both redeeming and unsavory light. John Proctor Is The Villain reveals the discourse can turn women on each other without men even needing to be in the room, monitoring us. We continue to define in greater detail what acts are cancelable, what punitive measures should be taken, what rehabilitation is feasible. The heartbreak of the central conflict in John Proctor is that the onus is on the girls to support, teach, our flawed and failing men. It’s the issue I’ve found myself battling in the toxic masculinity discourse: if there’s no one person to point a finger at, where does the fault fall? And how will men and boys ever participate in the healing?

Each passing year since 2018 has been rife with sexual abuse lawsuits by celebrities, studio executives, politicians, coaches and college athletic directors against any sex. Maybe girlhood is something women long to recover because it felt pure, untarnished. Maybe it only existed that way for us because we couldn’t hear the remarks from leering men, didn’t know the signs we would eventually learn about our predators, didn’t know the first or secondhand stories of misogyny and abuse that force a girl to grow up faster than she should need. Infantilizing ourselves, however, only saves us from accurately defining the acts of infantilization meant to wear women down.

The rage these girls felt at their teen male counterparts’ incompetence or blithe ignorance was palpable — and for an audience demographic heavily skewed towards women in their mid-late twenties, laughable. We know they can get away with this behavior because they have mothers who adore them and expect little of them, perhaps fathers or male figures who encourage the ‘just boys being boys’ culture.

The core group of girls wanted to be understood without having to do the actual work of ‘learning’ their teen boy counterparts — like many exhausted feminists, they longed for the boys to figure it out themselves and be intrinsically motivated to change. The audience laughed at their one-liners because we know those slacker boys: we had attempted to overcome someone’s weaponized incompetence at one point in our lives but have likely given up. We laughed because we have moved past the times of wasting all our breath and kindness and inclusivity and tears when the world we live in does not reward us.

The NYT review of Good Night and Good Luck concluded, “Preaching to the converted can be a good role for theater. So is rousing the demoralized with the example of heroes who have prevailed.” Even when an audience is converted, so to speak, it doesn’t directly equate to their taking action. People need reminders to not only absorb the knowledge, but to practice it so as to preserve it.

Journalism has lost all integrity and morality in the public sphere. We can’t read anything without questioning where the bias exists. As publications have lost their stronghold and media progressively reveals that it absolutely can be bought, the American public have lost sight of who holds the torch of truth.

While John Proctor seeks to use emotive empowerment for teen girls, Good Night and Good Luck brings the fact checkers face to face with government officials who abuse their power. In an unexpected turn to Broadway, George Clooney adapted his 2005 film of the same name for the stage, complete with a live taping in collaboration with CNN. The play follows Edward Murrow’s historic on-air showdown with Senator Joseph McCarthy, who at the time was harnessing the country’s fear of communism to take down political opponents in government, education and entertainment.

Perhaps he felt reviving the story in part because his personal life is imitating his art. Due to his connection to his wife Amal Clooney’s storied career in human rights law, as well as his active support in these endeavors, Clooney has been repeatedly scrutinized and threatened by the Trump administration. Separately, within his own party Clooney broke rank to voice his caution against incumbent Biden running for a second term. Finding the truth and standing up for it are imminent themes for the star and showrunner, and by representing the story of one powerful voice he hopes to mobilize the masses for an engaged citizenry.

“It’s a good thing to remind ourselves that we’ve been afraid before and we survive these things and we will get through it,” Clooney told Deadline. “The most important thing you can do is to constantly challenge people in power. You have to or they win.”

The Broadway we see today uses a certain point (or multiple) of history to say something about what’s happening in front of us. History is not told in the past tense here; it lives, breathes, and repeats itself. Some of these productions, like Cabaret, have created new twists and iterations based on the sociopolitical discourse each Broadway or West End season it is set within. When Alan Cumming took charge as the emcee in the 1993 production, the emphasis to highlight the efforts to protect queer civil rights transformed the production’s impact on culture. This year marks the first time a black man has been cast as the eEmcee — and while the esteemed Billy Porter first auditioned for the part in its initial 1960s run, only now has the West End accepted his argument that black people had always existed and experienced Nazism fall over Berlin.

Known to be an immersive show, Cabaret intends the audience to be implicated in the moral conflict of cast members like Sally Bowles and Frau Schneider, who readily choose self-preservation over the risk of fighting against the Nazi regime taking over Berlin. Political apathy is rife in America and across social media and attaches itself to increasingly dark consequences. Antisemitism, Islamophobia, and racist immigration raids are enabled by disengaged electorates who sit in disbelief at atrocities and their capacity to drive change. Cabaret is a cautionary tale — that actually happened, lest we forget — that apathetic individuals will one day collect into something that evil can swallow whole. Its return to the stage is further confirmation that we are watching it in real time.

Nowadays, the intersectionality of suffering within Hitler’s death camps seems obvious. When Cabaret was first coming to fruition, however, there was worry that the discourse around genocide across all minority groups would take away from the specific warnings against antisemitism; or even be too obvious a connection to the existing threats of segregation, police brutality and lynching outside the theatre doors.

Director and producer Hal Prince brought an image of shirtless young men snarling at the camera to rehearsal for the original production, noting that his cast the photo from a recent Life magazine issue as Nazi Germany — the image really capturing white supremacists protesting the integration of a public school. From the onset, Cabaret emphasized the present horrors were then, and are now, in parallel to the Holocaust.

How much time do we have before the curtain falls over us, so to speak? Can scripts, stage design, and choreography tear it down? That’s not me being facetious — maybe it’s possible. In order for our liberation to persist, so too must art, in its frivolity and gravity alike.

Dissenters have always posed the argument against whatever art forms they deem vapid or floozy as distracting from the true mission of a movement. But to pin down the definition of liberation without accepting its diversity is missing the point of being free. Cole Escola winning the Tony (and incredible levels of stardom) for Oh Mary!, a queer revisionist narrative that would certainly make a former First Lady roll in her grave, stands equal to its peers who aren’t taking the piss in this writer’s view. Sadie Sink triumphantly flailing across the floor to Lorde’s Green Light and Fosse’s offbeat hedonism in the Kit Kat Klub are powerful calls to action in today’s uneasy climate. The theatre is a skilled operative at baking activism into its shiny, shimmering musical numbers and quick wit.

Witch hunts old and new have hit Broadway to high praise and crowds who are lapping up every drop, and it’s no coincidence that they’ve all sprung up in the same season. Reaching to pull across multiple periods of fear-mongering and truth-seeking, the aforementioned shows are sewing together a call for collective resistance. A platform that draws crowds for its storytelling and showmanship can make dazzling resolutions out of even the darkest realities.

Ryann Stutz is a writer and marketing specialist based in Brooklyn obsessing over good omens in the form of Dalmatians, her memorable stint living in London, and Audrey Hepburn’s Givenchy pillbox hats in Charade. Her Substack, And I’ve Been Saying That!, interrogates the existing world order as it relates to fashion, politics and culture.

Instagram: @ryannstutz